Woman Around Town: Posted on December 11, 2024 by Carolyn Swartz in Dining Around

If your kitchen is anything like mine, you have many more gadgets, pots, pans, and utensils you actually use – at least on a regular basis. After checking with a few friends who also cook, I discovered that they, too, have catch-all drawers so cluttered and disorganized, they sometimes can’t open them without wrestling aside the wayward handle of a tool.

I continue to wash, fold, and return to the drawer dishtowels in a state of wretchedness I would never accept in my or my husband’s underwear or socks. If you wake me up at 3 a.m. to ask about the five 9″ and 10″ fry pans I have stacked at the back of a pull-out cabinet, I’ll insist that I need them all. Not only because each fills a somewhat different purpose, but what if 20 people were to suddenly show up for a bacon-and-eggs breakfast?

Here’s the rub: getting rid of certain old kitchenware in your crocks, cabinets and drawers isn’t easy. But that may be just what the doctor ordered – or would if she knew what they were made of and how they interact with heat and certain foods.

Plastic Utensils

In a recent piece in Wirecutter (The New York Times), Katie Okamoto wrote about the dangers of black plastic kitchen utensils— many of which, made from recycled electronic components, contain a “concerning” level of toxic chemicals, such as flame retardants. When these tools reach a certain temperature or interact with oily or acid-y foods, those chemicals can leach, or be released, into foods. You can read her piece if you want to see those chemicals spelled out, along with a litany of potential health threats. But we all know that leaching of chemicals into our food is not a good thing.

Okamoto does point out that not all plastic utensils contain such chemicals. Still, she says, it’s impossible to judge if they do by sight or feel alone. Experts, therefore, recommend tossing them out— replacing tongs, soup spoons, stirrers, and flippers with similar items made of wood, metal, and silicone.

Wood and metal have been around a long time. But silicone – not so much. Popular for its flexibility and softness, it’s considered “generally safe for everyday use” which also means “at reasonable temperatures.” Despite a name that sounds like silica, the Latin word for sand, silicone is not a natural product. Technically, it’s a plastic, a hybrid between synthetic rubber and a synthetic plastic polymer, mixed with a chemical additive derived from fossil fuels.

Like plastic utensils, silicone ones are also generally black, although you’ll find spatulas tips and baking trays in other colors. You can easily distinguish between the two because unlike plastic tools silicone feels rubbery and a little grippy—not hard and rigid.

Many cooks rely on silicone utensils for use on non-stick pans or tin-lined copper, both of which have more fragile surfaces than stainless steel, cast iron, and enamel. It’s important, however, to remember that the “reasonable temperature” upper reach for silicon is about 425° F. On a high-quality stove like a Wolf or Thermidor, you can easily find yourself flipping a steak that’s as hot as 500°. You probably already feel this in your bones: with something that hot, use metal or wood.

Silicone is believed to be safe for low-flame dishes like eggs and sauteed veggies. Likewise, it has been tested to be oven-safe, but again – only up to 425°. Still, given that the first silicone spatula was introduced in the 1990s, it hasn’t been around long enough for scientists to gather data from long-term studies.

Plastic Cutting Boards

Three or four decades ago, it was thought that plastic cutting boards were more hygienic than wood. After, all – unlike wood, you could simply put them in the dishwasher, confident that the endless cycle of hot water and soap would kill anything. New evidence refutes that, along with the wisdom of putting soft plastics into the dishwasher in the first place.

From nearly every point of view, plastic cutting boards are a bad choice They’re harder on your knives than wooden boards. Over time, they become scarred: lined with tiny fissures can trap bacteria. And when that happens, the degraded surface shed microplastic bits that can make their way into food. Wood, as it turns out, contains natural antimicrobial compounds that prohibit the growth of bacteria— as long as boards are properly cleaned and stored.

Proper cleaning means scrubbing your boards, often with an abrasive scouring pad or cloth (not Brillo) with dish soap under hot running hot water, drying immediately with a cloth towel, and storing them only once they’re completely air-dry.

To avoid cross-contamination, experts recommend using different boards for different food types: one for raw meat, another for fruits and vegetables, another for onions and garlic (more a matter of taste and smell than contamination). This is sensible. But not being that organized, I rely on thorough cleaning instead.

The one food I’m most concerned about is chicken – although few birds end up on my cutting boards. When they do, however, I take extra care in the cleaning. After a washing the board with soap and water, I make a paste out of kosher salt and lemon juice or water and rub it into the board before giving it another good rinse.

And speaking of chicken: the FDA strongly recommends against rinsing it before cooking. If you do that, you risk splashing pathogens in and around your sink, countertops, and faucet assembly, where— because you can’t see it you may not thoroughly clean it. Since cooking chicken kills any pathogens in any case, rinsing beforehand is a practice that’s not only dangerous but futile.

But back to cutting boards: now and then season with beeswax and/or food grade mineral oil. They’ll look prettier and last longer too.

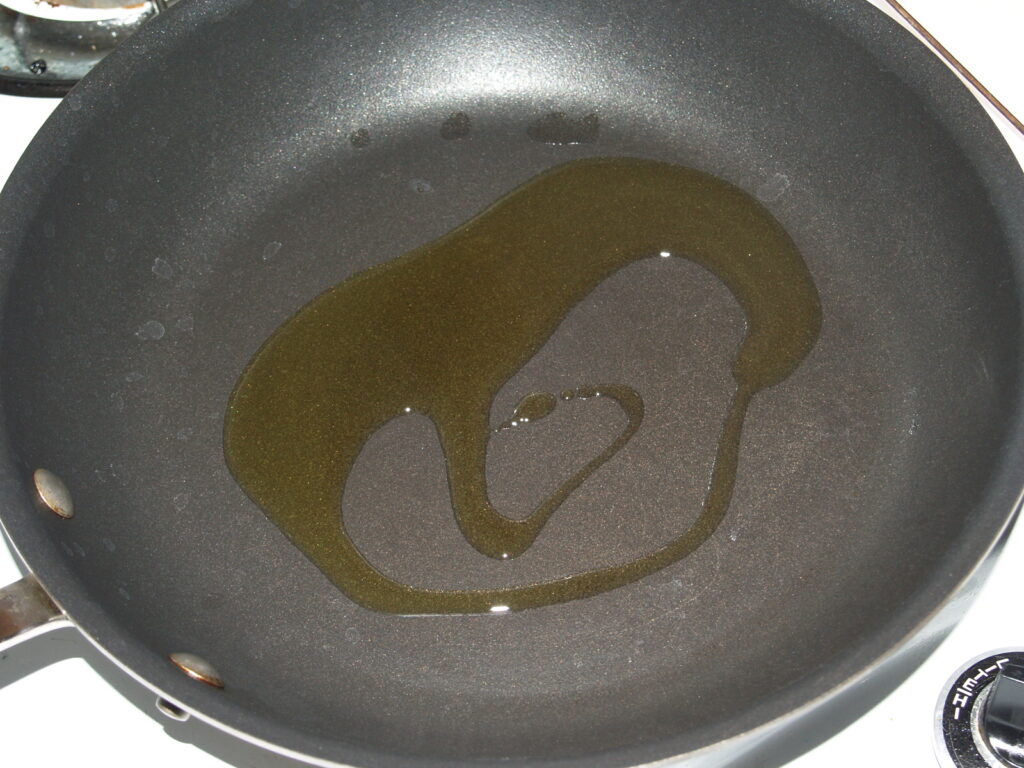

Non-Stick Pans

Even as materials improve and new generations of non-stick pans enter the market, the debate goes on. Although (like silicone) most are considered “generally safe for everyday cooking,” there are a few caveats to consider.

Avoid using nonstick at temperatures above 500°F as well as cooking times longer more than 45 minutes. At high temperatures, the coating of non-stick pans can break down and release toxic fumes. If your non-stick pan shows signs of flaking or scratching, or – in particular – if it’s more than 10 years old, it’s time to toss it and get a new one.

Stangoldsmith: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Pre-2014, some non-stick pans were still made with the chemical PFOA, used in making Teflon. Teflon was banned in the U.S. 2014. But PFOA has relatives and some manufacturers use them that will. This means that even a shiny new non-stick billed as “PFOA-free” may contain related chemicals will ultimately be proven harmful.

A well-seasoned cast-iron pan is reasonably non-stick — particularly old Griswolds that were machined smooth. Some newer manufacturers turning their back on pebbly and pre-seasoned. Tin-lined copper— which offers so many advantages in caramelizing of meats and fish—is also non-stick. Then, of course, there’s stainless, enamel-covered cast iron, and carbon steel, which is gaining in popularity.

I have to admit that I have relied on a good quality non-stick pan for low-flame cooking, such as scrambled eggs. But after writing this piece, it’s destined for the trash. I have no idea how old it is, but I’m guessing more than ten years. My son, who, with his fiancée, is bird-parent to a parrot, insists that certain non-stick pans, when heated to high temperatures, can actually kill an indoor bird. I won’t share the first thought that comes to mind. But the second brings vision of canaries in coal mines— which turns out to be plenty enough warning for me.

Open save panel

- Post